Sacrococcygeal Teratoma (SCT)

Sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT) is a tumor that forms on a fetus’ tailbone, also called the coccyx. The tumors are usually not cancerous (benign) but can be life-threatening if not treated.

What is Sacrococcygeal Teratoma (SCT)?

Sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT) is a tumor that forms on a fetus’ tailbone, also called the coccyx. The tumors are usually not cancerous (benign) but can be life-threatening if not treated.

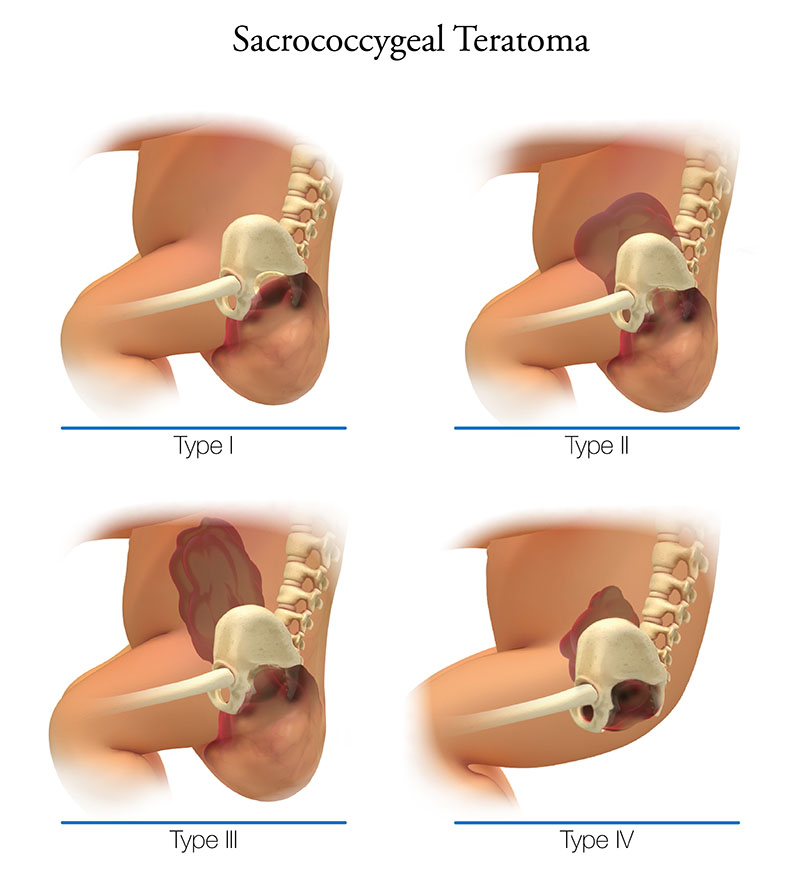

Sacrococcygeal tumors are categorized based on where they are and what they are like:

- Type 1 – The tumor is outside the body and attached to the tailbone.

- Type II – The tumor is partially outside the body and partially inside the body, within the baby’s pelvis or abdomen (belly).

- Type III – The tumor is mostly inside the baby’s body but can be seen from the outside.

- Type IV - The tumor is completely inside the baby’s body and cannot be seen from the outside.

SCT is rare, occurring in about 1 in 35,000-40,000 births. They are more common in males than females.

What are the Symptoms and Complications Associated with SCT?

Sacrococcygeal tumors range in size and severity. Most of them feed on blood. This makes the tumor to grow fast and the heart to work harder. It also may increase amniotic fluid, causing it to build up in other areas of the body. When this occurs, the fetus can develop hydrops. This is a condition that can lead to heart failure and endanger the lives of both the mother and baby. Babies under 30 weeks of gestation rarely survive hydrops. Other problems may include urinary blockage or bleeding from the tumor.

Sacrococcygeal tumors range in size and severity. Most of them feed on blood. This makes the tumor to grow fast and the heart to work harder. It also may increase amniotic fluid, causing it to build up in other areas of the body. When this occurs, the fetus can develop hydrops. This is a condition that can lead to heart failure and endanger the lives of both the mother and baby. Babies under 30 weeks of gestation rarely survive hydrops. Other problems may include urinary blockage or bleeding from the tumor.

In extreme cases, fetal hydrops can also lead to maternal mirror syndrome. This is when the mother’s condition looks like that of the sick fetus. The mother may have symptoms associated with preeclampsia, such as high blood pressure, protein in the urine, fluid retention, swollen feet and hands and vomiting. This syndrome puts her at risk for early (preterm) labor and delivery.

What Causes SCT?

The cause of SCT is not known.

How is SCT Diagnosed?

SCT is typically found when a maternal blood test shows a high level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). This can mean a tumor is present. It can be diagnosed by ultrasound. When the mass is outside the body, it may be seen on a routine ultrasound during the second trimester of pregnancy. More often, however, an ultrasound is ordered because the uterus is larger than normal.

If the doctor thinks your baby has SCT, you may be referred to a fetal center for special testing and care. Other diagnostic tests and procedures may include:

- Anatomy ultrasound – A high-resolution ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis and look at the mass.

- Doppler ultrasound – A test that measures blood flow to the tumor or other relevant fetal anatomy.

- Fetal MRI or low-dose CT – Non-invasive imaging techniques to get a clear, more detailed image of the tumor and fetal anatomy.

- Fetal echocardiogram – A special ultrasound to look at how the baby’s heart looks and works.

- Amniocentesis/chromosome studies – A medical procedure in which a small amount of amniotic fluid is taken and studied to screen for genetic problems.

Sometimes SCT is not diagnosed until the baby is born. In this case, an external tumor will be spotted quickly during a physical exam. Babies with an internal tumor may be diagnosed a few days later when they show symptoms, such as not being able to pee (urinate), constipation or lower back pain.

How is SCT Treated During Pregnancy?

You and your baby will be closely monitored by a fetal medicine specialist during your pregnancy. Prenatal management incudes frequent ultrasounds to track the size and effects of the tumor.

If the tumor stays small, your baby may not be treated until birth. However, when testing shows heart failure, fetal intervention may be considered.

If the gestational age is more than 28 weeks, your baby will probably get steroids. This helps the lungs develop and prepares the fetus for an early delivery. If the gestational age is under 28 weeks, your doctor may recommend fetal surgery to remove the tumor.

Fetal surgery options include:

- Open fetal surgery – The tumor is removed, or reduced in size, through an incision in the mother’s abdomen and uterus. The procedure, performed under general anesthesia, treats the condition and the heart failure.

- Laser ablation – The fetal surgeon inserts a thin needle into the mother’s abdomen and uterus, and eventually the fetus. A laser fiber is threaded through the needle and into the tumor. The energy from the laser destroys the blood vessels. This reduces blood flow to the tumor to slow its growth. It also treats the heart failure.

Fetal surgery is only done when the baby’s life is in danger. It is possible that fetal surgery can harm the fetus or induce premature labor.

Delivery with SCT

Babies with small sacrococcygeal tumors may be delivered vaginally. If the tumor is large or there is a lot of amniotic fluid, your doctor may recommend a Cesarean (C-)section to prevent the tumor from bursting or bleeding. Some of these cases may be delivered early and/or have ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT). EXIT is a procedure where the baby’s head is delivered and the upper part of the body stays attached to the placenta. This lets the surgeon look at the tumor and remove it before completing the delivery, if needed. This is done to avoid bleeding.

Babies with SCT should be delivered in a hospital that is prepared to treat newborns with rare birth defects and mothers at high risk for problems. This allows the mother and baby to have access to a team of neonatal and pediatric specialists, a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and pediatric surgical services.

How is SCT Treated After Birth?

Babies who are born with a SCT will need surgery to remove the mass and the tailbone to keep the tumor from coming back. Surgery is usually done a few days after birth and is followed by a stay in the NICU. Newborns will stay in the NICU until their lungs are working normally and their condition is stable.

While most sacrococcygeal teratomas are non-cancerous (benign), babies with cancerous (malignant) tumors will need other treatment from a child cancer doctor, called a pediatric oncologist, and other specialists.

What are the Long-term Effects of SCT?

Most babies with SCT develop normally after the tumor is removed and do not have lasting health problems. There is a small chance, however, for long-term problems. These include problems with peeing (urination) or constipation, which is typically managed with medicine. It is rare, but the tumor can return and need more treatment.

During early childhood, your baby will stay under the care of a pediatric surgeon who will monitor their health through regular physical exams, blood tests and imaging.