Creating a Model for Supporting Children of Incarcerated Parents

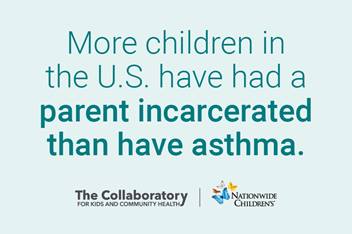

There are nearly 10 million children in the United States who have had a parent or guardian incarcerated. Those children have an increased risk of everything from language and developmental delays to depression and anxiety.

That’s not to mention the chaos of family, housing and economic instability that can come with incarceration.

For the last two years, Nationwide Children’s Hospital has been working to address what is sometimes called a “silent epidemic.” Its physicians and researchers have published what appears to be a first-of-its-kind guide to the issue, including recommendations for health care providers.

And the hospital has now created what could be the first dedicated program among United States children’s hospitals to help the families of these children and build stronger bonds between them and their loved ones who are incarcerated. In its first 18 months, the program served over 80 children and saw 100 fathers finish fatherhood enrichment classes while incarcerated.

“When we started this, there was no manual about how to do it,” said Andre Davis, coordinator of the Children of Incarcerated Parents project at Nationwide Children’s. “We needed to figure out who these children were, what they needed, and how to provide it to them and their families.”

Andre Davis is the coordinator of the Children of Incarcerated Parents project at Nationwide Children’s.

The hospital has recently finished a pilot of this program, made possible in partnership with the Franklin County Office of Justice Policy and Programs. A federal grant helped the county, Nationwide Children’s and other collaborators begin services.

Among the most difficult challenges is just identifying the children, said Davis. National statistics indicate that a hospital the size of Nationwide Children’s would see thousands of children of incarcerated parents every year. But unless those children or their families disclose their situations, there is no way to know if they have a loved one who is incarcerated.

Davis began working with members of Nationwide Children’s Primary Care Network, who would tell him when someone had self-disclosed. He and his colleagues would also visit Franklin County jails and halfway houses to let them know how he could help.

“I would say, ‘I am with Nationwide Children’s Hospital. I don’t care why you are here. I care about your children and about getting them resources,’” Davis said. “Based on that, the men in the jails would often sign up.”

Davis would connect with the families of those children, even if those families didn’t have a good relationship with the person who was incarcerated. The hospital’s Children of Incarcerated Parents project is part of the hospital’s larger Healthy Neighborhoods Healthy Families initiative, which includes many economic, housing and community supports.

Davis could link families with behavioral health care, free tax preparation services, hospital staff members who could help navigate school districts’ Individualized Educational Plan process, or emergency funds from the hospital’s Center for Family Safety and Healing.

Over time, he and other hospital staff members came to realize that they would have more consistent contact with parents who are at the Franklin County Community-Based Correctional Facility, a residential prison diversion program, than at the county’s jails. Davis could also help families get in-person visitation time, which was more difficult in the jails.

The last two years have been a good start, he said. The Children of Incarcerated Parents program is undergoing a strategic planning process now in an effort to bring more resources to more children and families, and to help everyone do a better job of identifying the children who need help.

“A lot of what we have been able to do so far is take care of immediate needs, without necessarily helping families develop the tools they need to have better outcomes in the long term,” said Davis. “We all want to build an infrastructure so that we can have an ongoing, meaningful impact."

“When we started this, there was no manual about how to do it. We needed to figure out who these children were, what they needed, and how to provide it to them and their families.”